Sunday, June 7, 2020 – Graffiti

- Mary Reed

- Jun 8, 2020

- 10 min read

When I walk the trail around Brookhaven College, there are two metal tunnels under the street to walk through. The ribbed metal seems like a difficult place to draw graffiti, but that is what I see. Made me wonder how drawing graffiti on public spaces started.

According to Wikipedia, early modernist graffiti can be dated back to boxcars in the early 1920s yet the graffiti movement seen in today's contemporary world really originated through the minds of political activists and gang members of the 1960s. It was used by gangs such as the Savage Skulls, La Familia and Savage Nomads to mark territory. The "pioneering era" of graffiti took place during the years 1969 through 1974. This time period was a time of change in popularity and style. Towards the end of the 1960s, the signatures—tags—of Philadelphia graffitists Cornbread, Cool Earl, Sketch and Topcat 126 started to appear. Cornbread is often cited as one of the earliest practitioners of modern graffiti.

Around 1970–71, the center of graffiti innovation moved to New York City, where graffitists following in the wake of TAKI 183, Tracy 168 and PHASE 2 would add their street number to their nickname, "bomb" a train with their work and let the subway take it "all city" — along with their fame, if it was impressive or simply pervasive enough. TAKI 183 was a youth from Washington Heights, Manhattan who worked as a foot messenger. His tag is a mixture of his name Demetrius (Demetraki), TAKI, and his street number, 183rd. Being a foot messenger, he was constantly on the subway and began to put up his tags along with his travels. This spawned a 1971 article in the New York Times titled "'Taki 183' Spawns Pen Pals." Bubble lettering held sway initially among graffitists from the Bronx, though the elaborate writing Tracy 168 dubbed "wild style" would come to define the art. The early trendsetters were joined in the 70s by graffitists like Dondi, Zephyr ad Lady Pink.

Also taking place during this era was the movement from outside on the city streets to the subways. Graffiti also saw its first seeds of competition around this time. The goal of most graffitists at this point was having as many tags and bombs in as many places as possible. Graffitists began to break into subway yards in order to paint as many trains as they could with a lower risk, often creating larger elaborate pieces of art along the subway car sides.

By 1971 tags began to take on their signature calligraphic appearance because, due to the huge number of participants, each participant needed a way to distinguish themselves. Aside from the growing complexity and creativity, tags also began to grow in size and scale – for example, many graffitists had begun to increase letter size and line thickness, as well as outlining their tags. This gave birth to the so-called "masterpiece" or "piece" in 1972. Super Kool 223 is credited as being the first to do these pieces.

The use of designs such as polka dots, crosshatches, and checkers became increasingly popular. Spray paint use increased dramatically around this time as graffitists began to expand their work. "Top-to-bottoms", works which span the entire height of a subway car, made their first appearance around this time as well. The overall creativity and artistic maturation of this time period did not go unnoticed by the public – Hugo Martinez founded the United Graffitists in 1972. UGA consisted of many top graffitists of the time and aimed to present graffiti in an art gallery setting. By 1974, graffitists had begun to incorporate the use of scenery and cartoon characters into their work. TF5 (The Fabulous Five), was a crew which was known for their elaborately designed whole cars.

New York City

Mid 1970s

By the mid-1970s, most standards had been set in graffiti writing and culture. The heaviest "bombing" in U.S. history took place in this period, partially because of the economic restraints on New York City, which limited its ability to combat this art form with graffiti removal programs or transit maintenance. "Top-to-bottoms" evolved to take up entire subway cars. A notable development was the "throw-up," which is more complex than simple "tagging" but not as intricate as a "piece." Not long after their introduction, throw-ups led to races to see who could do the largest number in the shortest time.

Graffiti writing was becoming very competitive and graffiti participants strove to go "all-city," or to have their names seen in all five boroughs. Eventually, the standards set in the early 1970s began to stagnate, and in the 1980s graffitists began to expand and change the subculture as described in the 1984 book Subway Art.

The late 1970s and early 1980s brought a new wave of creativity to the scene. As the influence of graffiti grew beyond the Bronx, a movement began with the encouragement of Friendly Freddie. Fab 5 Freddy (Fred Brathwaite) is another popular graffiti figure of this time, who started in a Brooklyn "wall-writing group." He notes how differences in spray technique and letters between Upper Manhattan and Brooklyn began to merge in the late 70s. Out of that came wild style. Fab 5 Freddy is often credited with helping to spread the influence of graffiti and rap music beyond its early foundations in the Bronx, and making links with the mostly white downtown art and music scenes. It was around this time that the established art world started becoming receptive to the graffiti culture for the first time since Hugo Martinez's Razor Gallery in the early 1970s.

Decline

Just as the culture was spreading outside New York City and overseas, the cultural aspect of graffiti in New York City was said to be deteriorating almost to the point of extinction. The rapid decline in writing was due to several factors. The streets became more dangerous due to the burgeoning crack epidemic, legislation was underway to make penalties graffiti vandalism more severe, and restrictions on paint sale and display made shoplifting more difficult. Above all, the Metropolitan Transit Authority greatly increased its anti-graffiti budget. Many favored painting sites became heavily guarded, yards were patrolled, newer and better fences were erected, and buffing of pieces was strong, heavy, and consistent. Stainless steel, to which paint adheres poorly —and was easily removed by the powerful cleaning solutions and spinning brushes used in automatic car washers at the yards — had also become the car body material of choice for new rolling stock, retiring hundreds of worn out carbon-steel bodied subway cars whose exteriors had made an ideal canvas for taggers. As a result of rolling stock being harder to paint, more graffitists went into the streets, which is now — along with commuter trains and box cars — the most prevalent form of writing.

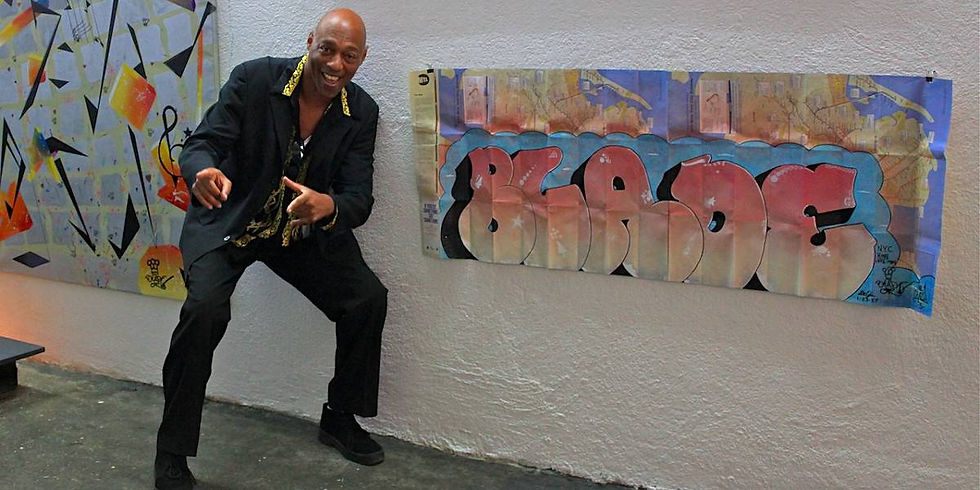

Many graffitists, however, chose to see the new problems as a challenge rather than a reason to quit. A downside to these challenges was that they became very territorial of good spots, and strength and unity in numbers became increasingly important. Some of the mentionable graffitists from this era were Blade, Dondi, Min 1, Quik, Seen and Skeme. This was stated to be the end for the casual New York City Subway graffitists, and the years to follow would be populated by only what some consider the most "die-hard" graffitists. People often found that making graffiti around their local areas was an easy way to get caught so they traveled to different areas.

1985-1989

The years between 1985 and 1989 became known as the "die-hard" era. The last shot for the graffiti participants of this time was in the form of subway cars destined for the scrap yard. With the increased security, the culture had taken a step back. The previous elaborate "burners" on the outside of cars were now marred with simplistic marker tags which often soaked through the paint.

By mid-1986 the MTA and the Chicago Transit Authority were winning their "war on graffiti," and the population of active graffitists diminished. As their population lowered, so did the violence associated with graffiti crews and "bombing." Rooftops also were being the new billboards for some '80s graffitists.

Clean Train Movement

The Clean Train Movement started in May 1989, when New York City attempted to remove all of the subway cars found with graffiti on them out of the transit system, as they brought in new graffiti-free rolling stock. Much controversy arose among the streets debating whether graffiti should be considered an actual form of art. Videograf Productions was the first graffiti video series to document the New York City's clean train movement. Prior to the Clean Train Movement, the streets were largely left untouched not only in New York City but in other major American cities as well. After the transit company began diligently cleaning their trains, graffiti burst onto the streets of America to an unsuspecting, unappreciative public.

During this period many graffitists had taken to displaying their works in galleries and owning their own studios. This practice started in the early 1980s with practitioners such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, who started out tagging locations with his moniker SAMO (Same Old Shit), and Keith Haring, who was also able to take his art into studio spaces.

In some cases, graffiti practitioners had achieved such elaborate graffiti (especially those done in memory of a deceased person) on storefront gates that shopkeepers have hesitated to cover them up. In the Bronx after the death of rapper Big Pun, several murals dedicated to his life done by BG183, Bio, Nicer TATS CRU appeared virtually overnight; similar outpourings occurred after the deaths of The Notorious B.I.G., Tupac Shakur, Big L and Jam Master Jay.

Graffiti is one of the four main elements of hip hop culture, along with rapping DJing and break dancing. The relationship between graffiti and hip hop culture arises both from early graffitists practicing other aspects of hip-hop, and it's being practiced in areas where other elements of hip hop were evolving as art forms. Occasional hip hop paeans to graffiti could still be heard throughout the 90s in tracks like the Artifacts' "Wrong Side of Da Tracks", Qwel's "Brick Walls" and Aesop Rock's "No Jumper Cables."

Saint Louis

A regularly scheduled event called Paint Louis is held annually in St. Louis. Paint Louis brings together graffitists from around the world to paint for two days as a celebration of the craft to paint on the longest continuous wall to make the "longest mural in the world."

Public opinion

Graffiti proponents perceive it as a method of reclaiming public space or displaying an art form; their opponents regard it as a nuisance, or as costly vandalism requiring abatement. Graffiti can be viewed as a "quality of life" issue, and its detractors suggest that the presence of graffiti contributes to a general sense of squalor and a heightened fear of crime. Graffiti has a strong negative influence on property values and lowers the tax base, reducing the available funding for municipal services, such as schools, fire protection and sanitation.

In 1984, the Phildelphia Anti-Graffiti Network was created to combat the city's growing concerns about gang-related graffiti. PAGN led to the creation of the Mural Arts Program, which replaced often-hit spots with elaborate, commissioned murals that were protected by a city ordinance, with fines and penalties for anyone caught defacing them.

Philadelphia's Broad-Ridge Spur also features a long-standing example of the art form at the Sprig Garden (to 8th and Market). While still existing, it has long been quarantined and features tags and murals that have existed for upwards of 15 years.

Advocates of the broken window theory believe that this sense of decay encourages further vandalism and promotes an environment leading to offenses that are more serious. Former New York City mayor Ed Koch's vigorous subscription to the broken window theory promoted the aggressive anti-graffiti campaign in New York City in the early 1980s, resulting in "the buff" — a chemical wash for trains that dissolved the paint. New York City has adopted a strenuous zero tolerance policy ever since. However, throughout the world, authorities often treat graffiti as a minor-nuisance crime, though with widely varying penalties. In New York City rooftops became the mainstream graffiti location after graffiti on trains died out.

In 1995 New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani set up the Anti-Graffiti Task Force, a multi-agency initiative to combat the perceived problem of graffiti vandals in New York City. This action began a crackdown on "quality of life crimes" throughout the city, and one of the largest anti-graffiti campaigns in U.S. history. That same year Title 10–117 of the New York Administrative Code banned the sale of aerosol spray-paint cans to children under 18. The law also requires that merchants who sell spray paint must either lock it in a case or display the cans behind a counter — out of reach of potential shoplifters. Violations of the city's anti-graffiti law carry fines of $350 per incident.

On January 1, 2006, in New York City, legislation created by council member Peter Vallone Jr. attempted to make it illegal for a person under the age of 21 to possess spray paint or permanent markers. The law prompted outrage by fashion and media mogul Marc Ecko who sued Mayor Michael Bloomberg and council member Vallone on behalf of art students and graffiti artists. On May 1, 2006, Judge George B. Daniels granted the plaintiffs' request for a preliminary injunction against the recent amendments to the anti-graffiti legislation, effectively prohibiting (on May 4) the New York Police Department from enforcing the restrictions. A similar measure was proposed in New Castle County, Delaware in April 2006 and passed into law as a county ordinance in May 2006.

Chicago's mayor, Richard M. Daley created the "Graffiti Blasters" to eliminate graffiti and gang-related vandalism. The bureau advertises free cleanup within 24 hours of a phone call. The bureau uses paints — compatible with the city's color scheme — and baking-soda-based solvents to remove some varieties of graffiti.

In 1992, an ordinance was passed in Chicago that bans the sale and possession of spray paint and certain types of etching equipment and markers. The law falls under Chapter 8-4: Public Peace & Welfare, Section 100: Vagrancy. The specific law (8-4-130) makes graffiti an offense with a fine of no less than $500 per incident, surpassing the penalty for public drunkenness, peddling or disrupting a religious service.

The Chicago Transit Authority has begun suing graffiti vandals that have been caught to recover the clean-up costs, and in some cases, the vandals have to clean up the graffiti as well. The agency loses about $1 million in vandalism costs each year.

In 2005, the city of Pittsburgh implemented a customized database-driven graffiti tracking system to build evidence for prosecution of graffiti suspects by linking tags to instances of graffiti. One of the first suspects to be identified by the system as being responsible for significant graffiti vandalism was Daniel Motano, known as MFONE. He was dubbed "The King of Graffiti" for having tagged close to 200 buildings in the city and was later sentenced to two and one-half to five years in prison.

Rapid City, South Dakota contains a section of the city known as Art Alley, a back alley in the downtown district between Main Street and Saint Joseph Street and stretching from 6th to 7th Street. It first began to properly form around 2005 and has expanded since. While graffiti is largely illegal in Rapid City and there are no ordinances condoning it, Art Alley is purposefully overlooked by law enforcement and cleanup crews and relies on the community of artists and landowners to add to and maintain the space. The alley has become quite popular for tourists and has become a cultural center for the city.

Comments